How to Feed Baby Birds?

Finding a baby bird can stir up strong emotions. You want to help, but you might feel unsure about what to do next. This guide will walk you through everything you need to know about feeding and caring for these tiny creatures.

Should You Really Feed That Baby Bird?

Before you rush to help, take a moment to assess the situation. Many baby birds you find outside don’t actually need rescuing. Parent birds often continue feeding their young even after they leave the nest.

Look at the bird carefully. Does it have feathers? Can it hop around? If yes, this is a fledgling. Fledglings are supposed to be on the ground. They’re learning to fly, and their parents are watching nearby. The best thing you can do is leave them alone.

Now, if the bird has no feathers or very few, it’s a nestling. Nestlings belong in the nest. Check nearby trees and shrubs for a nest. If you find it and can safely reach it, gently place the baby back inside. The myth about birds rejecting babies that smell like humans is false. Birds have a poor sense of smell.

You should only intervene if the bird is injured, the nest is destroyed, or you’ve waited several hours without seeing parent birds return. Cold weather and predators pose real threats to abandoned nestlings.

Preparing to Feed a Baby Bird

Once you’ve determined the bird truly needs help, contact a wildlife rehabilitator immediately. These professionals have the training and permits to care for wild birds. Search online for “wildlife rehabilitator near me” or call your local animal control office.

While you wait for professional help, you’ll need to keep the baby warm and safe. Baby birds can’t regulate their body temperature well. Create a makeshift nest using a small box lined with paper towels. Never use terry cloth or fabric with loose threads because tiny claws get caught in them.

Place a heating pad set on low under half the box, or use a hot water bottle wrapped in a towel. The bird should be able to move away from the heat if it gets too warm. Keep the box in a quiet, dark place away from pets and children.

What Baby Birds Eat in the Wild

Different bird species eat different foods. Knowing what type of bird you have helps you provide appropriate nutrition. Songbirds like robins, sparrows, and finches eat insects, worms, and sometimes berries. Hawks and owls are raptors that eat meat. Doves and pigeons eat seeds and grains.

Parent birds don’t just drop food into their babies’ mouths. They partially digest the food first. This process breaks down proteins and makes nutrients easier for the tiny digestive systems to absorb. You can’t replicate this exactly, but you can come close with proper food preparation.

Emergency Food Options

You should never feed a baby bird bread, milk, water, or seeds. These foods can kill them. Bread offers no nutrition and expands in their stomach. Milk causes severe digestive problems because birds are lactose intolerant. Water can easily go into their lungs instead of their stomach, causing aspiration pneumonia.

If you absolutely must feed the bird before reaching a rehabilitator, here are safer options:

For Songbirds: Mix high-protein dog or cat food (the canned, wet kind) with a small amount of water until it reaches the consistency of oatmeal. This mixture provides protein and is easier to digest than most household foods. You can also soak dry dog food in water until it becomes soft and mushy.

Hard-boiled egg yolk mixed with a tiny bit of water works in a pinch. The yolk contains protein and fats that growing birds need. Mash it thoroughly until no lumps remain.

For Raptors: Small pieces of raw meat work best. Cut chicken, turkey, or beef into tiny strips. Never season the meat or add any sauces.

For Doves and Pigeons: These birds drink crop milk from their parents, which is impossible to replicate at home. Puppy or kitten milk replacer mixed according to package directions offers a temporary solution. Baby bird formula from a pet store works even better.

How to Feed Baby Birds Properly

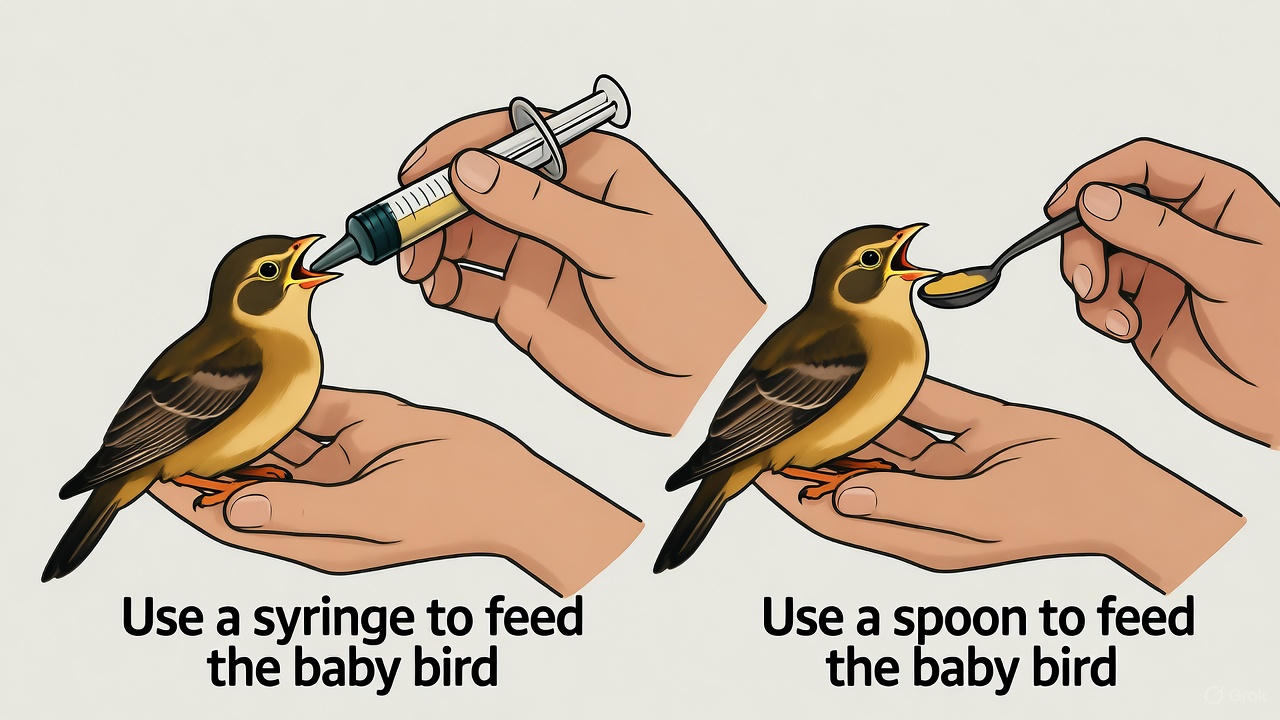

Feeding technique matters just as much as what you feed. Hold the food with tweezers or a small spoon. Never use your fingers because you’ll transfer oils and bacteria to the food.

Watch the bird’s behavior. Hungry babies open their mouths wide and make peeping sounds. This response is called gaping. If the bird doesn’t gape, it might not be hungry yet, or it might be too cold. Remember, cold birds can’t digest food properly.

Place small amounts of food deep into the mouth, toward the back of the throat. Aim for the left side of the throat where the esophagus opens. This technique prevents food from going down the windpipe. The portion should be about the size of the bird’s eye.

Feed the bird every 20 to 30 minutes from sunrise to sunset. Yes, this schedule is exhausting. Baby birds have incredibly fast metabolisms and need constant nutrition. This fact alone shows why professional rehabilitators are so important.

Never force-feed a bird. If it won’t eat, something is wrong. The bird might be too cold, too stressed, or seriously ill. Keep it warm and dark, and get professional help as quickly as possible.

Hydration Needs

Baby birds get most of their water from their food. The parents provide moisture through the insects and regurgitated food they offer. When you mix formula or wet food to the right consistency, you’re providing hydration at the same time.

You should never give water directly to a baby bird. Their feeding reflexes aren’t designed for drinking. Water easily goes down the wrong pipe, filling the lungs and causing death within hours. Even a single drop can be dangerous.

If the bird appears dehydrated (dry mouth, wrinkled skin, sunken eyes), moisten the food more than usual. You can also give electrolyte solution using a syringe, but this requires careful technique. Place drops on the side of the beak and let the bird swallow naturally. This method is risky and better left to professionals.

Signs Your Feeding Approach is Working

Healthy baby birds poop frequently. Their droppings should be firm in the center with white on the outside. After each feeding, you might see a fecal sac, which is waste wrapped in a membrane. Parent birds carry these away from the nest to keep it clean.

The bird should feel warm to the touch and stay active during daylight hours. Its skin should look pink and healthy, not gray or pale. Weight gain happens quickly when babies eat properly. You should see visible growth within days.

Feather development progresses steadily. Pin feathers emerge and unfurl into real feathers. The bird becomes more alert and starts exercising its wings. These signs indicate proper nutrition and care.

Common Feeding Mistakes to Avoid

Many well-meaning people make critical errors when feeding baby birds. These mistakes often prove fatal:

Feeding cold birds: A bird’s body temperature must stay around 102-106°F to digest food. Cold birds can’t process nutrients. Food sits in their crop and rots, causing deadly infections. Always warm the bird before feeding.

Overfeeding: Baby bird crops (the pouch in their throat where food collects) are visible. You can see when the crop is full. Stop feeding when you see a bulge. An overfilled crop can rupture or become impacted.

Using the wrong food: Hamburger, lunch meat, and processed foods contain too much salt and fat. Wild birds can’t handle these ingredients. Even foods that seem healthy, like mealworms from the bait shop, might be nutritionally inadequate or contain parasites.

Feeding sick birds: If a bird has labored breathing, won’t open its eyes, or feels limp, feeding it causes more harm than good. The bird needs medical treatment first.

Getting attached: Wild birds must stay wild to survive. Too much handling causes them to imprint on humans. Imprinted birds can’t be released because they lack the fear and skills needed to avoid predators and find food.

When Baby Birds Start Self-Feeding

The transition to independent feeding happens gradually. Fledglings begin pecking at food on their own around the time their flight feathers come in. This stage varies by species but typically occurs 2-4 weeks after hatching for small songbirds.

You can encourage this behavior by placing appropriate foods in a shallow dish. For songbirds, try small insects, berries, or moistened pellets. Raptors need small pieces of meat. The bird will watch you feed it, then try to grab the food itself.

Reduce hand-feeding sessions slowly as the bird eats more on its own. Keep offering food by hand if the bird seems hungry or isn’t gaining weight. Full independence takes time, and each bird progresses at its own pace.

Preparing for Release

Wild birds belong in the wild. Your goal is temporary care until the bird can survive on its own or a rehabilitator takes over. Birds ready for release can fly well, eat independently, and show fear of humans.

Never release a bird that can’t fly strongly. It needs to reach high perches to escape ground predators. Test flying ability in a safe, enclosed space first. The bird should be able to fly up and land precisely.

Release the bird in the same area where you found it, if possible. This location is likely within its parents’ territory. Release in the morning so the bird has a full day to orient itself and find food. Open the carrier and let the bird leave on its own terms.

The Legal Side of Caring for Wild Birds

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act protects most bird species in North America. This law makes it illegal to possess wild birds without proper permits. Only licensed wildlife rehabilitators can legally keep and care for protected species.

You can provide emergency care while transporting a bird to a rehabilitator. This exception exists because leaving an injured bird to die causes more harm than temporary human intervention. However, keeping the bird long-term, even with good intentions, breaks federal law.

Penalties for violations include fines up to $15,000 and possible jail time. These strict rules exist for good reasons. Inexperienced caregivers, despite their best efforts, often cause suffering through improper care. Birds also carry diseases that can spread to humans and domestic animals.

Finding Professional Help

Wildlife rehabilitators train for years to care for injured and orphaned animals. They understand species-specific needs, can identify illnesses, and know how to prevent imprinting. They also have relationships with veterinarians who specialize in avian medicine.

Start your search by calling local animal shelters and veterinary clinics. They keep lists of rehabbers in the area. State fish and wildlife departments maintain directories of licensed rehabilitators. The Animal Help Now website offers a search tool for finding wildlife help based on your location.

When you call, describe the bird’s condition clearly. Mention its size, coloring, whether it has feathers, and any visible injuries. The rehabber will tell you whether to bring the bird in or if it’s better left alone.

Some rehabbers offer phone coaching. They can talk you through emergency care if you can’t reach them right away. Follow their instructions carefully. They have experience you lack and want the best outcome for the bird.

Special Situations

Multiple babies: If you find several nestlings, keep them together. They keep each other warm and feel less stressed in a group. Feed each one individually, rotating through all the birds. Mark them with a tiny dot of nail polish on a toe if you need to track who ate last.

Injured birds: Visible injuries require immediate professional care. Don’t try to splint broken bones or treat wounds yourself. Keep the bird calm and warm while you arrange transport. Pain and shock kill birds quickly.

Very young hatchlings: Pink, naked babies with closed eyes are extremely fragile. They need professional care immediately. Their odds of survival are low even in expert hands. Do your best to find help quickly.

Night-time discovery: Birds found after dark pose a dilemma because rehabbers might not be available. Set up the warm box and wait until morning. Don’t try to feed the bird at night. It won’t eat in the dark anyway, and you might cause more harm than good.

The Emotional Challenge

Caring for a baby bird is emotionally draining. You invest time and energy into a creature that might not survive. Wildlife rehabilitation has a high failure rate, especially for very young birds. Even with perfect care, some babies are too weak or injured to make it.

Don’t blame yourself if the bird dies. You gave it a chance it wouldn’t have had otherwise. Many factors beyond your control influence survival. Disease, developmental problems, and injuries from the initial accident all play roles.

On the flip side, successfully raising a baby bird creates incredible satisfaction. Watching it fly away is bittersweet but rewarding. You helped preserve life and contributed to the local ecosystem. That contribution matters.

Why Birds Need Our Help

Human activity puts baby birds at risk. Outdoor cats kill billions of birds each year. Window strikes cause massive mortality. Habitat loss removes nesting sites and food sources. Climate change shifts breeding seasons and migration patterns.

When you rescue a baby bird, you’re compensating for these human-caused problems. Your effort won’t change global bird populations, but it matters to that individual bird. Every creature has value, and your compassion makes a difference.

We share this planet with incredible diversity. Birds control insect populations, pollinate plants, and spread seeds. Their songs add beauty to our days. Taking responsibility for the impact we have on their lives is the least we can do.

Long-Term Prevention

You can help birds even when you’re not rescuing babies. Keep cats indoors or supervise them outside. Put stickers or tape on windows to prevent collisions. Plant native flowers, shrubs, and trees that provide food and shelter.

Leave dead trees standing if they’re not a safety hazard. These snags become home to cavity-nesting birds like woodpeckers and bluebirds. Reduce pesticide use in your yard because insects feed baby birds. Even pretty lawns matter less than healthy ecosystems.

Support conservation organizations that protect bird habitat. Vote for policies that address climate change and preserve wild spaces. Teach children to respect wildlife and observe birds from a distance. These actions create lasting positive impacts.

Final Thoughts

Feeding baby birds is challenging work that’s best left to professionals. If you find yourself in a situation where you must help, keep the bird warm, avoid common mistakes, and contact a wildlife rehabilitator as soon as possible. Your quick action and proper temporary care can make the difference between life and death.

Remember that most baby birds on the ground don’t need rescuing. Parent birds do a better job than even the most dedicated human. Step back and observe before intervening. Real emergencies require fast action, but patience serves you well in most situations.

The tiny bird in your hands depends on you to make good decisions. By following these guidelines, providing appropriate emergency care, and getting professional help quickly, you give that baby its best chance at a full life in the wild where it belongs.